Your Cart is Empty

FREE U.S. DOMESTIC SHIPPING ON ALL ORDERS OVER $199 •100% MONEY-BACK GUARANTEE• Lifetime Access • No Subscription

FREE U.S. DOMESTIC SHIPPING ON ALL ORDERS OVER $199 •100% MONEY-BACK GUARANTEE• Lifetime Access • No Subscription

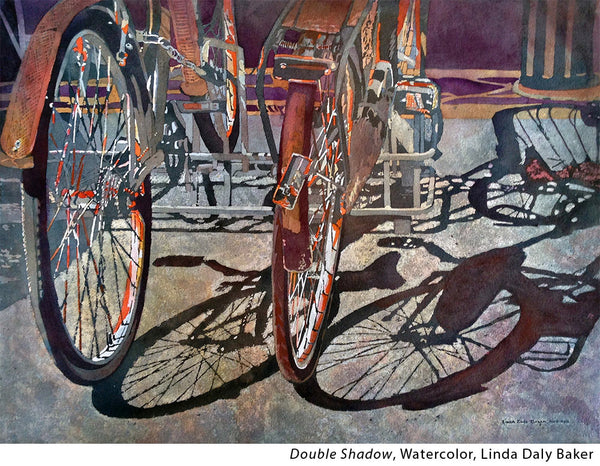

Linda Daly Baker has a primary goal she brings to her watercolors. She wants to capture the extraordinary light that transforms a subject almost to abstraction. As a full time artist, her work combines her love of white, nuanced greys and rich earth tones. Baker is a sought after workshop instructor and juror and her paintings have been featured in magazines both nationally and internationally. She has two videos with Creative Catalyst including Layers of Design in Watercolor and Fearless Watercolor: Layering and Color.

What is it that watercolor gives you as an artist?

When I was an art major in college they did not teach watercolor but one day someone had some in class and I zipped out a quick floral. I was hooked!! I loved the way the paint felt on the paper and the magic that happened with adding just a bit of water. From that point forward, I knew no matter what type of art I made, there would always be a place for watercolor.

Why do you think watercolor has the reputation for being difficult? Why (or why not) is it deserved?

As a purist, I use neither white nor black so any white is the white of the paper and any black is a mix of rich, deep colors. This alone makes watercolor more difficult.

Watermedia on the other hand allows white and layering so as a media is more forgiving. When holding out the whites, it requires more planning and less spontaneity if you want the whites in certain places.

Of course, the better you become, the more tools you acquire as an artist and the better able you are to manipulate the paint and solve the design problems more effectively. Most paint styles allow you to cover it with another layer but with watercolor, too many indecisions end up looking muddy and disorganized.

Walk us through your process? What do you need to have figured out at each stage?

As for me, I am a planner. This is not necessarily required, but it is the way I prefer to work.

I start with an idea, work out a value sketch, and draw. Once I reach that point, I mask any small areas that I would like pure white, and then pour three liquid colors over the entire painting.

I generally use a triad, and most often a pure blue, red, and yellow. When the colors mingle on the page, they can make the most amazing colors not to mention the design principles that get handled. This process will automatically give my painting unity, harmony, and a sense of order as an underpainting.

After drying, I will repeat the process of applying more masking fluid and then pouring colors. Each layer gets a bit darker and more rich and the shapes that are covered with masking give it depth.

When I have applied as many layers as I want, I remove all the masking with a rubber cement remover and then fine tune with direct painting and removing and scrubbing. Sometimes, I take off more than I add in terms of lost and found edges, and creating a bit of mystery but having some things less defined.

Why is planning important for you? How does it allow you to work later on? What’s the danger in skipping the planning part of a painting?

In my workshops, I often say ‘failing to plan is planning to fail’ so the prep work is probably the most important part of my process.

Planning a value sketch becomes a sort of road map for the fun process of pouring. If you do not work out the composition ahead of time, it is harder to get the elements you need later in the process. When starting with a sketch, you can fine tune your composition ahead of time.

For example, preventing arrows leading the eye off the page, making sure the focal point is well placed, making certain all the corners are different, and so on. But more importantly than working our composition is defining a value pattern.

Dominance of value is one of the most important considerations in the planning process. Knowing where you want light, mid, and dark ahead of time takes much of the guesswork out of painting. I sometimes say that I plan intensely so I can paint with abandon. If I short the planning stage, I will have to be much more conscious of the paint application and it will not be as fun! Painting with abandon is pure fun!

How important is it to understand materials with watercolor painting? Why?

Because of my pouring process, it is very important for me to understand the qualities of the paints. Because I do so much layering, it is important that I pour with colors that are as transparent and translucent as possible. The more opacity a color has the bigger chance for a muddy buildup in the painting. I stay away from stainers because they are hard to correct and tend to grab the paper more than lay on the surface which is what I am attempting with my paint.

Brushes are important as I want a soft brush without much bristle action so as to not disturb the layers of pouring when I direct paint.

Paper matters as a soft very absorbent paper does not work as well as a harder surfaced paper that can be more of a workhorse. All the pouring and sometimes extreme brushwork is hard on the paper and the sizing needs to hold up.

What kind of pigment qualities are you looking for in your paints? (For example, do you use transparent, semi-transparent or opaque paints?) Why? What do those pigments give your work?

For my pouring process, I am seeking the most transparent of colors. So what is interesting is that different brands produce different opacities. For instance in one brand, cerulean blue will be opaque and another, it might be transparent.

Today, it is more important than ever to actually look at the color charts put out by the different manufacturers. I avoid cad colors, opaque, sedentary, and stainers. This still leaves a beautiful array of luminescent colors.

Another thing that works well with my process is to pour with paints that are a bit less intense and save higher intensity paints for any direct paint finishing. Pouring with a less intense paint allows for more layers of thin luminosity without a heavy build-up of color.

Composition can seem like an overwhelming concept. Where does someone start learning composition?

After all these years of painting and competing, I still learn about composition everyday. Some concepts I learned from books and workshops, but actually, I believe I have learned the most from personal experience.

For years, I have painted everyday and spent the first few of those years, attempting to stay within the guidelines of composition. Sticking with the guidelines tends to make a more comfortable painting and sells better through galleries. When I started competing, I would intentionally move outside the guidelines for a bit of shock value or in an attempt to be different and grab a jurors attention.

Today, I just paint what I feel like! My advice is to live in your sketchbook! Take a subject and design many different compositions. Play around with different value patterns. Do the same subject but emphasize line. or play with more extreme shapes. The more time you spend with your sketchbook, the more you will understand the general guidelines. I have spent years teaching composition in my workshops and now offer it online. It is amazing how much information there is and I could discuss composition forever.

I think artists with less experience are a bit afraid of composition but it is truly the backbone of all art.

How important is drawing? What does being able to draw give you as an artist?

Years ago, when I made the bold decision to quit my day job and become a full time artist, I gave myself challenges to bring my skill level up fast. One of my challenges was that I would draw at least 1/2 hour everyday. I would sketch the spaghetti cooking on the

stove, the kids working on their homework, absolutely anything. What I knew for sure, was thatI did not want to be limited in what I would paint by an inability to draw.

Being able to draw has given me the confidence to attack complex subject matter and my love of pattern on pattern, on pattern would not be possible without my ability to draw.

You’re not afraid to tackle complex subjects. How do you design your work so that it keeps the viewer’s eye engaged but not overrun?

When you are a pattern painter, there are many approaches that help the viewer. I refer to it as transportation through the painting. I use a lot of triangles. Triangles of shape, color, or even size and scale. A triangle inside a rectangle or a square gives you visual transportation as your eye goes from one shape to another and discourages the eye from leaving the painting. Another help is depth which is attained through value. Having some of the patterns darker, or softer, or use of lost and found are all ways to keep the patterns from looking flat. The last thing I will mention is attempting to have a resting space in the painting. If the eye has a place to rest visually, it is more engaging. The important thing is that the pattern not be flat and all the same.

What’s the biggest thing you see your students struggling with? What advice do you give them?

I think the biggest thing I mentor students with is finding their own personal vision and voice. As a frequent juror, I am saying repeatedly to show us something different, something unique, something ordinary in a unique way, something we haven’t seen before. Creativity is hard to define and the art muse is illusive. The more you ‘play’ with a subject, or idea, the more ways you explore it, the better chance you have of developing a style. What is a style? I would say when you look at a painting and say, ‘I would know your paintings anywhere’ you have developed a style.

I would like to say one last thing about a style. It is my belief that your style finds you and not the other way around. So, when I see an artist’s body of work, I can usually tell which workshops they have taken and often who’s work they aspire to. But many times, in the back of their portfolio, will be some doodles and this is usually where I find the artist.

The more you paint, your style will find you in the way you hold your brush, or your natural mark, or even the amount of pressure you apply to your brush. The colors that you automatically are drawn to and the way you apply them play into your voice as an artist. It might be important here to say that borrowing a style is not a good idea. Just because you like the way that someone else paints, or you are enamored by their subject choices, does not make them yours. Workshops are a place to learn new tools to add to your toolbox. Take those little jewels and use them your own way. All of these things put together make up who you are as an artist and define your style.